Shopping for Bollywood films is both science and art form. Rare is

the film you can walk to Walmart or Target or other major store and buy on DVD

(3 Idiots is perhaps the one exception). There are Indian groceries that carry

a motley mix of pirated and legitimate, but mostly pirated. If you are very,

very lucky, there is perhaps an Indian DVD store. But their selection is never

expansive, nor guaranteed, and seeking a particular title is often an exercise in

futility.

There are libraries, but their duties are first to books and then

to DVDs and VHS. I have made some great finds at libraries, but there too it is

useless to hunt for a specific title.

The new releases quickly show up streaming on Netflix and

Einthusan, but the older titles are often hard to find online, especially if

you require subtitles.

There are sites like Induna and ErosEntertainment.com to buy DVDs,

and almost everything is on Amazon these days. But there is little to no thrill

in that. It’s akin to those who complain about buying books on Amazon rather

than in a bookstore, only worse. Not only can you not feel the DVD, it feels as

though you haven’t given it the treatment necessary for such a rarity. You

haven’t searched for the treasure. You’ve merely picked it up and methodically

paid.

.

And so sometimes, the hunt for a particular title goes on, and on,

and on, and on.

For this reason, I still haven’t seen Sholay. Or Mother

India. Or Pakeezah. Or Anand. Or a half-dozen other things.

.

But for one classic, at least, my hunting has ended.

After two years of turning over DVDs in shops with hope, I finally

found Mughal-E-Azam at a sort of truck stop in middle-of-nowhere in

Rajasthan while busing from Jaipur to Delhi. This was the only DVD I bought in

my time in India, but if there was one to buy, I’m glad it was that.

After two years of turning over DVDs in shops with hope, I finally

found Mughal-E-Azam at a sort of truck stop in middle-of-nowhere in

Rajasthan while busing from Jaipur to Delhi. This was the only DVD I bought in

my time in India, but if there was one to buy, I’m glad it was that.

A period piece. A love story born of legend. Mughal history mixed

with said legend. Dilip Kumar, Madhubala, Prithviraj Kapoor. I had a very great

desire to see Mughal-E-Azam for many reasons. Two years of searching only made

it stronger.

.

The same for the elation I felt when I found it on my last day in

India, tucked among OMG and Student of the Year, which I spotted

first.

But even though the long wait to find Mughal-E-Azam was over, the

wait to watch it was not. Between uncharged laptops over 18 total hours of

flying and more than 18 hours of ensuing jetlag, it took me almost another week

to actually watch the film. (And even longer, you know, to write this post.)

.

But after two years, what was a few more days?

.

In a way I wondered, did the wait build an insurmountable

expectation for the film? But now I don’t think I even knew quite what I was

expecting. I knew vaguely the story of Anarkali and Salim, the court dancer and

the prince, because you can’t be around Indian culture without being exposed to

it in some form (even if it’s “Anarkali Disco Chali”). And I knew the film was

something of a revered classic.

I can understand why. Mughal-E-Azam is grand, as all things Mughal

must be (trust me: I’ve just come home from days spent in Mughalarchitecture), from sets to costumes to dialogues — all contributing to a beautiful film despite the questionable colorization. It is packed with legendary

performances and marvelous songs. And full of long dramatic scenes, such as

when Salim ascends to his place of execution for a solid five minutes while the

sculptor sings, “Zindabad! Zindabad! Mohabbat ae zindabad!” (“Long live,

long live, long live love.”)

And it has all the tenets of a great Indian story: forbidden love,

class differences, two doting mothers, family issues, the threat of

death, separation angst, an invocation of justice, a beautiful woman who could

be construed as a prostitute figure (with a heart of gold), sweeping statements

about the magnificence of Hindustan.

|

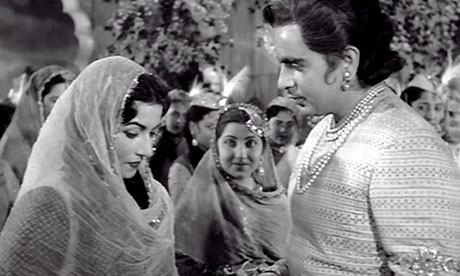

| Dilipji's soft smiles are enough to melt the heart. |

All it lacks is a happy ending (and even its ending is not so

unhappy as it might have been).

Mughal-E-Azam is instead a very cyclical story of repeatedly

self-sacrificing love.

Salim sacrifices his rights as prince and prepares to sacrifice

his life for Anarkali. Anarkali sacrifices her freedom for Salim — refusing to

even lie about their love to save herself — and ultimately is the one who

sacrifices her life (though she is spared at the last moment from entombment,

she must live in banishment and seems mostly unresponsive). Unlike the many

Bollywood love stories since, the obstacles to love in Mughal-E-Azam are

insurmountable, due to the unflinching power and stubborn will of Akbar — the Mughal so great he was known as Akbar-e-Azam, Great the Great.

|

| Akbar-e-Azam, Great the Great, is the real star. |

It would make an interesting contrast to watch Jodhaa Akbar and

Mughal-E-Azam back to back — reconciling Hrithik Roshan’s softened, in-love

Akbar with Prithviraj Kapoor’s resolute, heartless Akbar. (Jodhaa seems to have

less of a contrast since her love for Akbar is unwavering; Aishwarya Rai’s

Jodhaa simply has more youthful sass than Durga Khote’s, which is rather

understandable.)

|

| Father and son's one soft moment. |

Honestly, one of the great triumphs of Prithviraj Kapoor’s Akbar

is that he isn’t hateable, even when his actions are thoroughly loathsome. Who

wants to like a man who’s so concerned with imperial honor that he condemns his

own son to death? Nobody, of course. Except maybe some sadists. Yet, as

revealed in scenes like the tremor in his hands when he sends Anarkali to her

last night with Salim, Akbar isn’t the villain of the film. He’s just the

emperor, the rule-enforcer, the man-in-charge. The true Mughal. “I swear by

Allah I am not an enemy of love,” he tells Anarkali in the end, “but a slave of

principles.”

In a way, Salim seems to have inherited the same stubbornness,

though it is directed differently. Who else but a stubborn Mughal fights a war

he knows he’ll lose against an emperor, all in the name of a dancing girl?

Anyone else would have just taken the girl and run.

Anarkali, for her part, is equally stubborn. (Maybe all of the

stubborn people in this story really just deserve one another.) Who but one of

the world’s most obstinate people could remain still when an arrow was shot at

her? And when given a way out of imprisonment for loving above her station, Anarkali doesn’t just say “no thanks.” She

instead flaunts her feelings for Salim in front of Akbar … and everyone else.

But of course Madhubala carries it off with grace, cheek and

flair. Like every song and dance she does in the film. Full of emotions.

But of course Madhubala carries it off with grace, cheek and

flair. Like every song and dance she does in the film. Full of emotions. The same goes for all that Dilip Kumar radiates in both Salim’s

wordless looks of love and very verbal displays of defiance. The scene in which

he stumbles about drugged while realizing that he is losing Anarkali broke my

heart (while invoking shades of drunken Devdas-style desperation).

The same goes for all that Dilip Kumar radiates in both Salim’s

wordless looks of love and very verbal displays of defiance. The scene in which

he stumbles about drugged while realizing that he is losing Anarkali broke my

heart (while invoking shades of drunken Devdas-style desperation).

It certainly doesn’t hurt that Dilip Kumar is remarkably handsome

(because of or despite his perfectly coifed wig? All I can say Mughal-E-Azam is

the most attractive I’ve ever found him) and Madhubala legendarily beautiful.

Or, perhaps, that Mughal-E-Azam is an angst and hurt-filled love

story fueled by Dilip Kumar and Madhubala’s own heartbreakingly thwarted love

story. Both are stories of love versus principle in which principle ultimately

wins.

And so, in the end, the story leaves you with many emotions and

quite a bit of awe.

It’s only fitting, in a way, that Mughal-E-Azam was a film I had

difficulty finding. Nothing about the film seems to have come easy. It took

some 15 years from concept to completed project, nine of those years coming

after principal photography. Madhubala, already suffering from the heart defect that eventually killed her, fainted on set. Prithviraj Kapoor and

Dilip Kumar also suffered physically from carrying around full armor in high heat.

And, of course, Dilip Kumar and Madhubala broke up somewhere in the middle of

all that.

But some things are worth the wait and worth the suffering.

It's always heart warming to see someone appreciate a work of art like you have done here.

ReplyDeleteYou rightly noted that Akbar-e-Azam is the star here. If you have him as the founding father, if you will, of your khandan, it's no wonder that talent still lives in the fourth generation. But all said and done the original Kapoor was the only one with enough gravity to make things revolve around him just by being there. This movie needed him to balance the hot and steaming pairing of Dilip Kumar and Madhubala.

Hey, I do want to add one more thing to all that you said about the movie. The dialogues. Urdu is a language that naturally lends itself to beautiful phrases. And the dialogues were done by the eminent writers and the poets of the day. The dialogues are as much a star of the movie as anyone else. So much so that, though getting rarer now, you still can have some of the dialogues come up in a conversation among kids in small town India. And though these kids probably would know the name of the movie but certainly not the starts in it. The dialogues were the part of local lexicon when I was growing up. And I am not too old too.

Do look them up. I am not sure the subtitles would have done any justice to them.

If Akbar-e-Azam wasn't the star, they wouldn't have named the movie Mughal-e-Azam. :) And I'm a fan of Kapoors in every generation, but it is true that none of them quite have the gravitas of the original.

DeleteMy Hindi-Urdu comprehension level is still not what I'd like it to be, but I will say that the subtitles on Mughal-e-Azam were much better at keeping the poetics than other classic films I've watched. (For example, the subtitles when I tried to watch Pyaasa were a disaster.) I'm sure they still don't do the dialogues justice, but then neither does my rudimentary comprehension. Haha.

Hello sir

ReplyDeleteNice blog And Info Also Good That you can provide

Sir please update the latest page Info About Dilip Kumar Dialogues i want to need latest info for my School project ...

महाकालसंहिता कामकलाकाली खण्ड पटल १५ - ameya jaywant narvekar कामकलाकाल्याः प्राणायुताक्षरी मन्त्रः JANUARY 2026

ReplyDeleteओं ऐं ह्रीं श्रीं ह्रीं क्लीं हूं छूीं स्त्रीं फ्रें क्रों क्षौं आं स्फों स्वाहा कामकलाकालि, ह्रीं क्रीं ह्रीं ह्रीं ह्रीं हूं हूं ह्रीं ह्रीं ह्रीं क्रीं क्रीं क्रीं ठः ठः दक्षिणकालिके, ऐं क्रीं ह्रीं हूं स्त्री फ्रे स्त्रीं ख भद्रकालि हूं हूं फट् फट् नमः स्वाहा भद्रकालि ओं ह्रीं ह्रीं हूं हूं भगवति श्मशानकालि नरकङ्कालमालाधारिणि ह्रीं क्रीं कुणपभोजिनि फ्रें फ्रें स्वाहा श्मशानकालि क्रीं हूं ह्रीं स्त्रीं श्रीं क्लीं फट् स्वाहा कालकालि, ओं फ्रें सिद्धिकरालि ह्रीं ह्रीं हूं स्त्रीं फ्रें नमः स्वाहा गुह्यकालि, ओं ओं हूं ह्रीं फ्रें छ्रीं स्त्रीं श्रीं क्रों नमो धनकाल्यै विकरालरूपिणि धनं देहि देहि दापय दापय क्षं क्षां क्षिं क्षीं क्षं क्षं क्षं क्षं क्ष्लं क्ष क्ष क्ष क्ष क्षः क्रों क्रोः आं ह्रीं ह्रीं हूं हूं नमो नमः फट् स्वाहा धनकालिके, ओं ऐं क्लीं ह्रीं हूं सिद्धिकाल्यै नमः सिद्धिकालि, ह्रीं चण्डाट्टहासनि जगद्ग्रसनकारिणि नरमुण्डमालिनि चण्डकालिके क्लीं श्रीं हूं फ्रें स्त्रीं छ्रीं फट् फट् स्वाहा चण्डकालिके नमः कमलवासिन्यै स्वाहालक्ष्मि ओं श्रीं ह्रीं श्रीं कमले कमलालये प्रसीद प्रसीद श्रीं ह्रीं श्री महालक्ष्म्यै नमः महालक्ष्मि, ह्रीं नमो भगवति माहेश्वरि अन्नपूर्णे स्वाहा अन्नपूर्णे, ओं ह्रीं हूं उत्तिष्ठपुरुषि किं स्वपिषि भयं मे समुपस्थितं यदि शक्यमशक्यं वा क्रोधदुर्गे भगवति शमय स्वाहा हूं ह्रीं ओं, वनदुर्गे ह्रीं स्फुर स्फुर प्रस्फुर प्रस्फुर घोरघोरतरतनुरूपे चट चट प्रचट प्रचट कह कह रम रम बन्ध बन्ध घातय घातय हूं फट् विजयाघोरे, ह्रीं पद्मावति स्वाहा पद्मावति, महिषमर्दिनि स्वाहा महिषमर्दिनि, ओं दुर्गे दुर्गे रक्षिणि स्वाहा जयदुर्गे, ओं ह्रीं दुं दुर्गायै स्वाहा, ऐं ह्रीं श्रीं ओं नमो भगवत मातङ्गेश्वरि सर्वस्त्रीपुरुषवशङ्करि सर्वदुष्टमृगवशङ्करि सर्वग्रहवशङ्करि सर्वसत्त्ववशङ्कर सर्वजनमनोहरि सर्वमुखरञ्जिनि सर्वराजवशङ्करि ameya jaywant narvekar सर्वलोकममुं मे वशमानय स्वाहा, राजमातङ्ग उच्छिष्टमातङ्गिनि हूं ह्रीं ओं क्लीं स्वाहा उच्छिष्टमातङ्गि, उच्छिष्टचाण्डालिनि सुमुखि देवि महापिशाचिनि ह्रीं ठः ठः ठः उच्छिष्टचाण्डालिनि, ओं ह्रीं बगलामुखि सर्वदुष्टानां मुखं वाचं स्त म्भय जिह्वां कीलय कीलय बुद्धिं नाशय ह्रीं ओं स्वाहा बगले, ऐं श्रीं ह्रीं क्लीं धनलक्ष्मि ओं ह्रीं ऐं ह्रीं ओं सरस्वत्यै नमः सरस्वति, आ ह्रीं हूं भुवनेश्वरि, ओं ह्रीं श्रीं हूं क्लीं आं अश्वारूढायै फट् फट् स्वाहा अश्वारूढे, ओं ऐं ह्रीं नित्यक्लिन्ने मदद्रवे ऐं ह्रीं स्वाहा नित्यक्लिन्ने । स्त्रीं क्षमकलह्रहसयूं.... (बालाकूट)... (बगलाकूट )... ( त्वरिताकूट) जय भैरवि श्रीं ह्रीं ऐं ब्लूं ग्लौः अं आं इं राजदेवि राजलक्ष्मि ग्लं ग्लां ग्लिं ग्लीं ग्लुं ग्लूं ग्लं ग्लं ग्लू ग्लें ग्लैं ग्लों ग्लौं ग्ल: क्लीं श्रीं श्रीं ऐं ह्रीं क्लीं पौं राजराजेश्वरि ज्वल ज्वल शूलिनि दुष्टग्रहं ग्रस स्वाहा शूलिनि, ह्रीं महाचण्डयोगेश्वरि श्रीं श्रीं श्रीं फट् फट् फट् फट् फट् जय महाचण्ड- योगेश्वरि, श्रीं ह्रीं क्लीं प्लूं ऐं ह्रीं क्लीं पौं क्षीं क्लीं सिद्धिलक्ष्म्यै नमः क्लीं पौं ह्रीं ऐं राज्यसिद्धिलक्ष्मि ओं क्रः हूं आं क्रों स्त्रीं हूं क्षौं ह्रां फट्... ( त्वरिताकूट )... (नक्षत्र- कूट )... सकहलमक्षखवूं ... ( ग्रहकूट )... म्लकहक्षरस्त्री... (काम्यकूट)... यम्लवी... (पार्श्वकूट)... (कामकूट)... ग्लक्षकमहव्यऊं हहव्यकऊं मफ़लहलहखफूं म्लव्य्रवऊं.... (शङ्खकूट )... म्लक्षकसहहूं क्षम्लब्रसहस्हक्षक्लस्त्रीं रक्षलहमसहकब्रूं... (मत्स्यकूट ).... (त्रिशूलकूट)... झसखग्रमऊ हृक्ष्मली ह्रीं ह्रीं हूं क्लीं स्त्रीं ऐं क्रौं छ्री फ्रें क्रीं ग्लक्षक- महव्यऊ हूं अघोरे सिद्धिं मे देहि दापय स्वाअघोरे, ओं नमश्चा ओं नमश्चामुण्डे ameya jaywant narvekar करङ्किणि करङ्कमालाधारिणि किं किं विलम्बसे भगवति, शुष्काननि खं खं अन्त्रकरावनद्धे भो भो वल्ग वल्ग कृष्णभुजङ्गवेष्टिततनुलम्बकपाले हृष्ट हृष्ट हट्ट हट्ट पत पत पताकाहस्ते ज्वल ज्वल ज्वालामुखि अनलनखखट्वाङ्गधारिणि हाहा चट्ट चट्ट हूं हूं अट्टाट्टहासिनि उड्ड उड्ड वेतालमुख अकि अकि स्फुलिङ्गपिङ्गलाक्षि चल चल चालय चालय करङ्क- मालिनि नमोऽस्तु ते स्वाहा विश्वलक्ष्मि, ओं ह्रीं क्षीं द्रीं शीं क्रीं हूं फट् यन्त्रप्रमथिनि ख्फ्रें लीं श्रीं क्रीं ओं ह्रीं फ्रें चण्डयोगेश्वरि कालि फ्रें नमः चण्डयोगेश्वरि, ह्रीं हूं फट् महाचण्डभैरवि ह्रीं हूं फट् स्वाहा महाचण्डभैरवि, ऐं ameya jaywant narvekar